In a typical year at ISMIR, around 300 submissions are read and reviewed by 4 people each. This huge effort, expended voluntarily by fellow community members, is vital to ensuring the high quality of research published at ISMIR.

As researchers, we are all eventually called on to review the work of others. But what is expected of us as ISMIR reviewers?

For the most part, what's expected is communicated clearly: each year, reviewers are reminded of the ISMIR Reviewer Guidelines. Those new to reviewing may also want to read examples of ISMIR reviews (along with commentary and advice) provided by Tom Collins.

However, since reviewing is a solitary act, even experienced reviewers may wonder: how long do my peers spend writing reviews? How much of an expert on a topic should I be before I can review a paper about it? Does anyone else worry about the same things I do when reviewing?

To learn more about the secret art of reviewing, we sent an anonymous survey to all meta-reviewers from this year and last, asking these questions and more. In the rest of this post, we report the results.

To be clear, this is not intended to be an instruction manual for reviewers; instead, consider it an overview of how experienced ISMIR reviewers view this task.

Participants & Experience

To start with, we want to thank all the participants in the survey! We received 46 responses — roughly half of those invited — and it is clear that each respondent spent a lot of time to craft their responses to our sometimes specific, sometimes open-ended questions. Thank you!

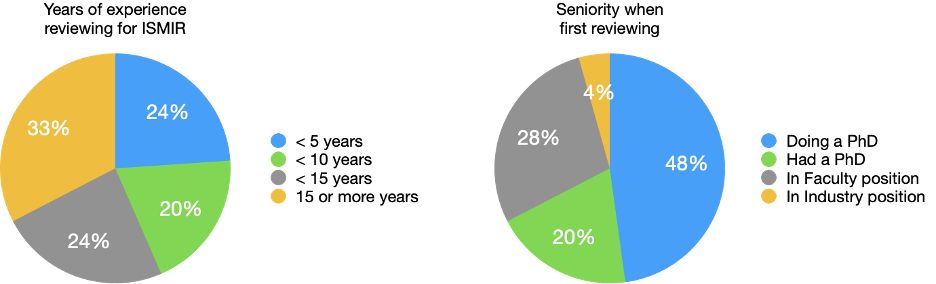

Question 1. How many years have you reviewed papers for ISMIR?

Responses were evenly distributed, with about a quarter of respondents in each 5-year band: 1–5 years; 5–10 years; 10–15 years; and 15–20 years.

Question 2. What was your level of seniority the first time you reviewed for ISMIR?

Almost half of reviewers started reviewing for ISMIR while pursuing a PhD, and another 20% had a PhD. Around 30% started while already faculty; perhaps they were faculty when ISMIR was founded, or perhaps they rose to a faculty level while focused on another field before joining the ISMIR community.

Questions 3–4. In what capacity have you reviewed papers for ISMIR? For other venues?

We invited 95 participants, who had all reviewed and meta-reviewed for ISMIR (or were about to meta-review for the first time). Of the 46 who responded:

- 15 had served as Scientific program chair for ISMIR;

- 45 had reviewed for another conference;

- 30 had meta-reviewed for another conference;

- 21 had served as Scientific program chair for another conference.

So, the respondents to this survey seem to skew toward the experienced end of meta-reviewers, and all seem equipped to put their experience reviewing for ISMIR in context with other venues.

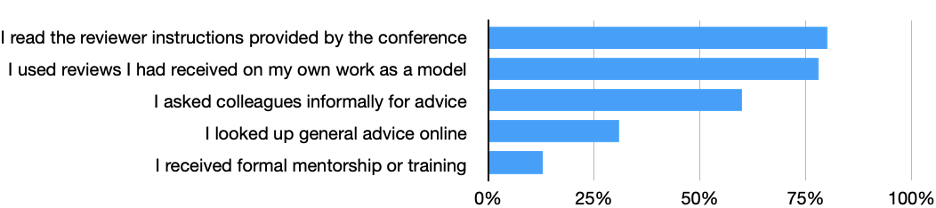

Question 5. How did you learn to review papers?

Here are the available responses, ranked by response frequency:

Most of this learning is passive: reading the instructions, and learning from the reviews one has received in the past.

Only two of the options ("asked colleagues", "formal mentorship") imply real contact with other people, and at least 34% of respondents did not select either.

Question 6. Have you ever felt unqualified to review a paper? What do you think makes someone a qualified reviewer?

Most respondents (at least 60%) owned up to sometimes feeling unqualified in some way:

"Absolutely! As a junior reviewer I would often feel overwhelmed and not fit to judge the work or more senior people (imposter syndrome)."

"Yes, and I have declined to review them as soon as I realised it."

"[Yes, but] this can be largely avoided when there is a proper bidding process."

Sometimes, this is reason enough to request a new reviewer. On the other hand, several said that some humility about one's expertise is important and not disqualifying:

"This happens very often, and is rather the normal case when [doing] interdisciplinary [work]."

"Yes, self-doubt is a part of the research process! Essentially, I think we should strive for truly "peer" reviews and not a senior vs. junior setup."

What does qualify a reviewer then? Responses varied, but a few themes pervaded: (1) some expertise on the subject matter; (2) knowledge of the expectations of the ISMIR community; (3) knowledge of scientific work and writing generally.

"A reviewer is qualified when the paper falls inside their area of expertise and they have experience in writing papers as lead authors."

"You need experience as a scientific writer. You need to acknowledge that there are many 'correct' ways of writing a paper, not just yours."

"I don't believe one needs to be a super-specialised expert to review a paper –– just one such review is sufficient –– but one does need to be in the target audience for the conference/journal."

"One needs knowledge of the topic, and an understanding of 1) the scientific method, and 2) the publication process."

"Expertise in relation to at least some aspects of a paper may be a criterion of being qualified, but then again papers should also be comprehensible for reviewers without expertise related to the subject of a paper."

Some respondents told us about strategies they use to inform authors and editors about their expertise:

"[If I feel unqualified, I will] either decline the invitation to perform the review […] or announce in the review form that I'm not qualified and will concentrate on the form of the paper (rather than the content); most important I will avoid making strong statements (such as Strong accept or Strong reject)."

"[…] I usually include a disclaimer at the beginning of the review that identifies the areas of the paper where I have less experience (topic, methods, etc.) so the meta-reviewer and authors can take that into account […]".

Reviewing Effort

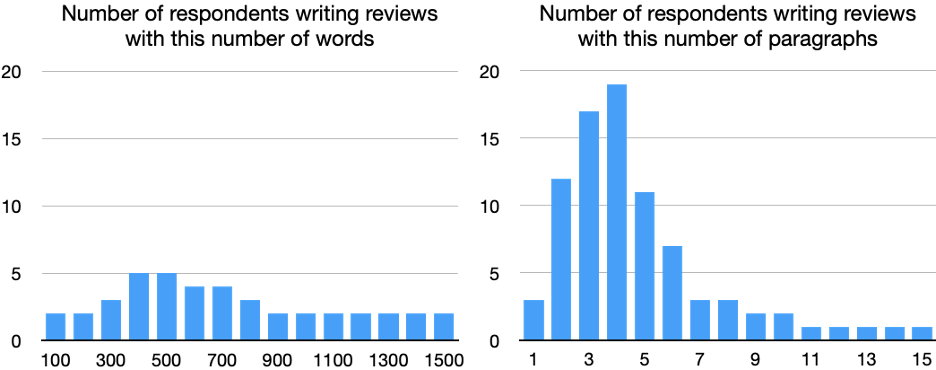

Question 7. How long are your ISMIR reviews?

For this question, respondents indicated their own unit: words, paragraphs, or pages. There was a lot of variation: some regularly write reviews as short as 100 words or 1–2 paragraphs; others regularly write 2-page reviews with over a dozen paragraphs.

However, the median length for each unit — 1 page, 3–5 paragraphs, 400–500 words — were also the most typical answers. These are all probably reasonable guidelines.

(In the above plots, an answer like "6–8 paragraphs" adds 1 to the height of columns 6, 7, and 8.)

Question 8. How long should reviews be?

When asked to recommend a length, respondents were split.

Around half ventured a concrete number. Of these, 90% gave the exact same length that they gave in the previous question, and the others gave something shorter.

The other half declined to offer a specific number. Of these, almost all used one of two phrases to explain why: "long enough" or "it depends".

"No specified length is needed — depends on the quality of the paper and the feedback required."

"As long as it takes to explain why the paper is good or bad."

"As long as they need to be to improve the paper."

"Long enough to help the committee make a reasoned decision and to give the authors helpful feedback."

"The length of the review fully depends on the quality of the work."

"I don't think there is a general appropriate length. This should be dependent on the paper. A very good paper with not much to criticize, or a barely readable paper should [not] need very long reviews, while borderline papers may require more content for further discussions with other reviewers/meta."

In other words: there is substantial variation in how long reviews are going to be, and many reviewers feel this variation is justified.

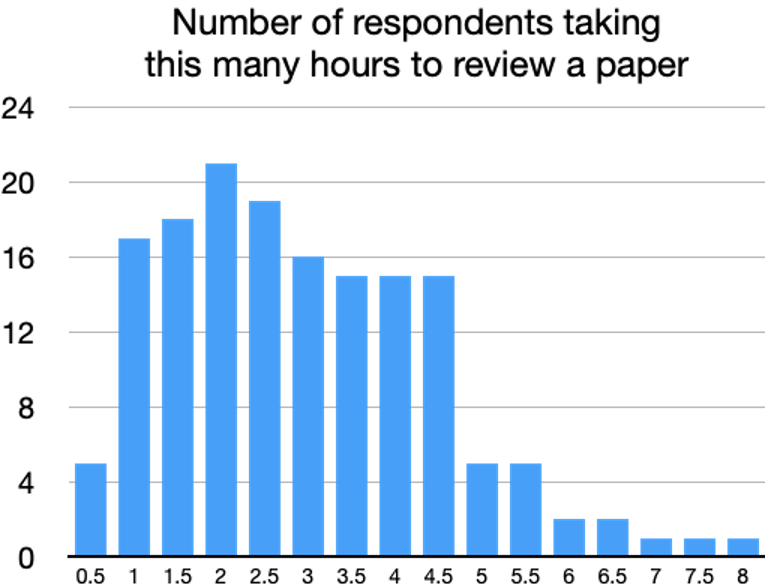

Question 9. How many hours do you spend on a review?

The average estimated time spent was 3 hours per review. We spend a lot of time reviewing ISMIR papers!

As ever, though, there was a huge amount of variation, with some estimating as little as 30 minutes and others as long as 8. (A few wrote "half a day", which I took to mean 6 hours.)

Many noted that the same caveat about review length applies here: "it depends."

"Depends on familiarity with [the] material and how easy the paper is to read."

"1-5 hours depending on [the] quality of paper."

"Between 4 and 8 hours, maybe more depending on the paper."

"Depends on how knowledgeable I am on the topic, how well the paper is written (readability), and how many comments I need to make; I guess, about 45 minutes per paper (I have never measured this)"

Also, many reviewers noted that they might not spend all this time in one go:

"Probably around 2 hours total: 60-90 minutes to read in detail, 30-60 minutes to write the review. That said, (ISMIR only) I find it helps to do the reviews before the deadline, and then come back to them a week or so later to give a second look and see if I feel the same."

"1/2 day (but spread over several days to have the time to think about the content)"

Question 10. How many hours should you spend?

Once again, most respondents indicated the exact same time here as in the previous question, although some indicated that spending an hour or two less is desirable.

"Would love to keep all reviews under 1 hour"

"I've been told that one can review in about 1-2 hours, but I just can't seem to go faster than 2-3 hours."

And, as ever, it depends!

"45 min to 90 min; does not need to be in one go — reading on one day, writing on another day is a good practice"

"Long enough to provide a critical, comprehensive, and helpful review"

To be continued

Unpacking down this survey turned into a larger project than anticipated, so we've decided to split the content into two installments. Please stay tuned for an imminent follow-up, which will cover what survey respondents felt about reviewing methods, handling problems, and reading others' reviews.