Last week, we discussed a survey that we circulated to meta-reviewers of the ISMIR conference. We presented the results of the first two sections of the survey, about the preparation reviewers have and the effort they put into reviewing. In this article, we present the results of the remaining sections of the survey. These questions covered methods used and problems faced by reviewers, as well as a couple questions about what reviewers do and don’t like about the reviews they receive.

As with the previous post, this is not intended to be an instruction manual for reviewers. Rather, we hope that insights from experienced reviewers can help others with their own reviewing workflow.

Reviewing Methods

Many expectations about how a review should be written are made clear in the ISMIR Reviewer Guidelines, but some additional basic recommendations are useful. For example:

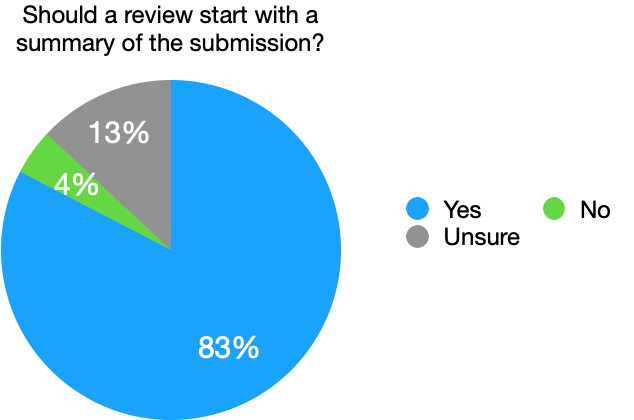

Question 11. Should a review start with a summary of the submission?

A majority of ISMIR reviewers polled (83%) agree with this widely recommended practice. By including a short summary, a reviewer signals to the submitter — as well as to their co-reviewers and the meta-reviewer — that they read the paper carefully.

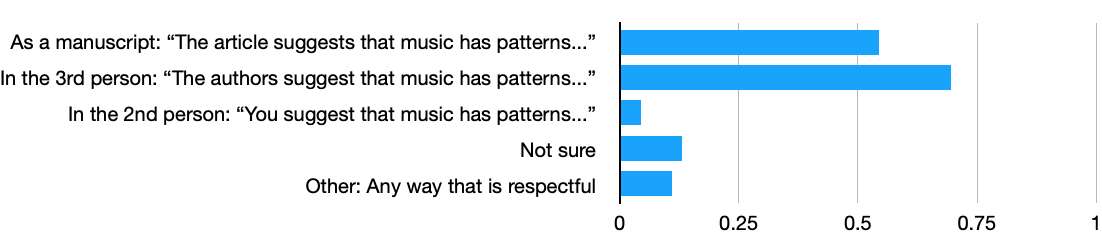

Question 12. How should a reviewer refer to the submission and its authors?

On this point, the ISMIR guidelines are clear: reviewers “may want to avoid referring to the authors by using the phrase ‘you’ or ‘the authors’, and use instead ‘the paper’.”

Reviewers agree that the 2nd person (“you”) isn’t a great way to refer to authors, and that referring to “the paper” is better. However, even more respondents feel that using the 3rd person (“the authors”) is acceptable as well.

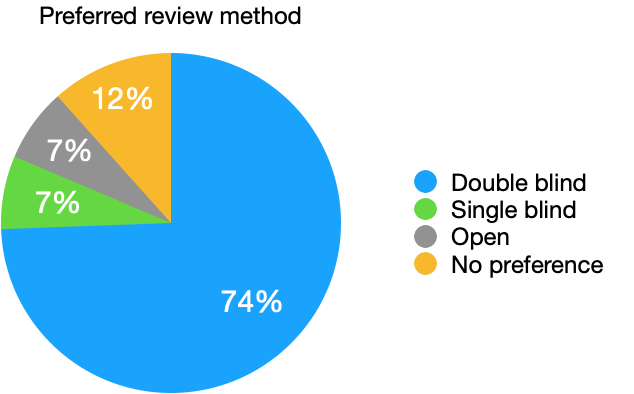

Question 13. Which level of anonymity do you prefer?

ISMIR has a double-blind review process (i.e., submissions are anonymous and submitters never learn the identity of the reviewers). Other conferences are single-blind (reviewers know the identities of the submitters) or open (reviewers and submitters know each others’ identities).

Respondents were largely in favour of ISMIR’s double-blind status quo, but about a quarter preferred or were open to an alternative approach.

At the end of the survey, we asked for general comments, and a few respondents returned to this issue. One commented: “open reviews […] are usually of better quality than private ones”, and that, thanks to the growing vogue for publishing pre-prints on arXiv, “blindness of reviews is often very debatable”. Another added that they sense “resistance to the idea that [students] can’t already put their work on arXiv […] making ISMIR a less attractive publication venue for them. Times are changing fast.”

However, not all agreed that a change in policy was inevitable; one proposed that “author guidelines should do more than ‘discourage authors’ of [publishing pre-prints], [and] forbid it during an ‘anonymity period’.”

Question 14. What is your method or process for reviewing?

For this question, we invited long answers — and got ‘em! Collectively, respondents wrote over 3000 words in their answers; this was more than double the word count for any other question.

The answers ranged from terse overviews — “I make a pass reading the paper and taking notes. Then I write the review.” — to section-by-section checklists:

“1. Understand the paper from headings and figures. 2. Abstract and conclusions — are they consistent? […] 3. Introduction — is the problem statement clearly defined? […] 7. Results — are results discussed or only presented? Are results discussed critically? […]”

The details of reviewers’ approaches varied greatly: for example, we know that writing a summary is recommended (see Question 11), but reviewers write them at different times:

- At the outset: “[…] I start writing my review. I write a short summary.”

- In the middle: “Then after a full pass [of making comments], I write a summary of the paper, and try to synthesize my small comments into general comments.”

- At the end: “The last thing I do is write the summary of the review.”

However, the methods also had a lot in common. A few key strategies cropped up regularly:

First, many described skimming and re-reading: “skim over abstract” and “glance at figures and captions” to get a “sense of organization”, before “read[ing] the paper taking notes.” The first pass serves to “identify the point of the paper and how it sits with respect to prior work”; the second to “focus on details, […] logical flow of argument,, whether the conclusions follow from presented evidence/arguments, etc.”

Second, many described “taking notes in two sections in parallel”, which are ultimately sorted into “major and minor comments”, or lists of “big-picture issues” and “minor errors”. For the latter, some prefer to “include page and line numbers where possible”. Organising these comments is important for making a coherent review: one explained that they “arrange [their bullet] points so that they follow a coherent story” and then “write the whole review around those bullet points.” As another put it: “I spen d thirty minutes or so to […] organize my criticisms into a coarse ‘taxonomy’.”

Third, many emphasized taking time in between reading and reviewing : e.g., after a first pass of reading and taking notes, one reviewer will “put [it] away for a day or two”; others do the same to “sit with it for a while” or “to think about the content of the paper”, and “some days later write a paragraph on what the paper is presenting.” One said after finishing their review, they “wait a week or so, […] and read my review again and see if I still feel the same about it.”

Question 15. How would you describe the standard of acceptance for an ISMIR paper?

The intended meaning of this question was: “What [in your words] are the essential criteria for acceptance at ISMIR?” However, only 8 respondents took it this way! Of these, the most often-cited criterion was novelty (5), with insight, relevance, importance, validity and writing quality also cited.

But the question was ambiguous, and most respondents (31) took it to mean either “What is the average quality of accepted ISMIR papers?” or “What is the quality / consistency of reviewing at ISMIR?”

Regarding the quality of ISMIR papers, most felt happy and described it as “high”; one said they had “seen many conference with half the acceptance rate [of ISMIR] but lower standards.” Others qualify this, saying ISMIR does “not follow very high standards in ingenuity and execution” — although some say “this is a strength […] as it allows discussing a broad variety of papers.”

Regarding ISMIR reviews, reactions were mixed. Some wrote that the “review process is of good standard,” and that reviews are “constructive [and] above the average for other conferences in my field.” Others were more critical, describing reviews as “a little on the lax end” or “a bit random,” “like a lottery,” so that review quality “really depends on the reviewers you get.” Some noted the tension that can arise “when you have […] musicologically oriented papers vs some signal processing oriented papers,” saying that this has “made it hard for there to be clear standards of acceptance,” with reviewers perhaps being “tougher on technical papers.” One wrote:

“I had [a] paper rejected because the problem scenario was deemed not realistic while this is something we considered using in my company.”

This sentiment may be changing over time: a few respondents shared the view that reviewing quality “was better when the conference was smaller,” and that they “no longer attach […] the intellectual weight to ISMIR acceptance/rejection” that they used to. Describing their experience with the discussion phase where reviewers are meant to debate the merits of a paper, one wrote:

“During the discussion phase, many reviewers […] defend their reviews under the assumption that the acceptance threshold is sufficiently low to justify cursory reviews. (Exactly the opposite should be the case: the lower the acceptance rate, the more careful the reviews should be.)”

Problems and advice

Question 16. What is the best way to handle a paper that has an overwhelming number of problems?

This may not be a common occurrence, but as some respondents noted, “critiquing those papers can be hugely frustrating.” If a reviewer were to “go into detail with every single little thing, it [would be] too overwhelming for reviewer and author.”

Instead, it is best “to stay positive and assume good faith.” Be “clear and direct, but also be encouraging to the authors, as they may be early-stage researchers with important potential.” Put another way: “Conference reviewing should be somewhat pedagogical in nature […] the tone of the review should be positive and constructive”; “paper rejections should be productive learning experiences,” not “attacks on [people’s] legitimacy as researchers.”

How, then, to write a constructive but clear rejection? “Focus on larger structural issues and provide suggestions on how to improve” the submission; “provide a clear path to the authors for how to rewrite the paper and/or which experiments they should focus on before rewriting.”

How much to write? Most suggested keeping it relatively brief: a “very clear and short comment” can suffice, as “only the [problems] that make the paper prone to get rejected need to be detailed.” One reviewer advises, “Don’t worry about typos or language issues” — just “identify the largest problems and suggest remedies if possible.” Another disagreed, saying it was important to recommend “ways to address those problems in detail: a short review that only broadly summarizes these problems might not be useful to the authors.”

Question 17. On occasions where you have been assigned a review you feel unqualified for, what have you done?

In Question 5, we asked about feeling unqualified in a general sense. In this question, we narrow the focus: if you feel unqualified to review a particular paper, or suspect a mismatched assignment, what should you do?

Most respondents said that they had been in this situation, and they took an array of actions:

- “Asked meta-reviewers and editors to re-assign the paper.”

- “Offered to do the review for another paper on a paper where I am better qualified.”

- “Delegate[d] to competent colleagues.”

- “Tried to find someone to help me.”

- “Read some papers on related subjects published in recent years.”

- “Lowered my ‘reviewer confidence level’.”

- “[Wrote] a review from an ‘outsider’ perspective, which I [stated] clearly in my review.”

One respondent wrote that this happened to them as a meta-reviewer: “In this instance, I requested the strongest possible reviewers that I could and leaned on their expertise.”

On the other hand, one wrote that “there is almost always value in the feedback of a generally knowledgeable person” to evaluate the “accessibility, structure, presentation quality, broad interest, etc.”

Question 18. What piece of advice would you give to someone reviewing ISMIR papers for the first time?

This question turned up a gold mine of advice. Some of the most frequently doled advice:

- “Start early.”

- “Take your time.”

- “Read the reviewer guidelines and examples!”

First-timers especially should “seek help from colleagues (e.g. by asking for sample reviews),” or even “ask your supervisor [to] check your review before submitting it.”

Several advised keeping an upbeat, open attitude:

- “Be empathetic.”

- “*You may criticize the work, but you can’t criticize the authors.8”

- “Try to open up your perspective, do not impose your particular way of doing things and your own research ideas into the review.”

- “Don’t feel the need to prove yourself by being overly critical in your review.”

- Treat “the paper as [if] it were [your] own shared work and [you] wanted to improve it.”

Remember “to write the review not only for the author but also for the editor/program chairs.” To best help the committee, “don’t just say it is great or bad, but explain why you think so.”

While it is clear that reviewing should be treated seriously, several respondents advised calm: “Don’t spend too long agonizing or writing for hours.” One explained:

“You know more than you think! It’s the authors’ job to make you understand their work, and so if you’re confused, that’s not a failing on your part. Rather, it’s valuable feedback for the authors.”

Getting feedback

For these final questions, we asked respondents to think about how they feel as authors rather than as reviewers.

Question 19. What do you dislike most about the reviews you receive?

By far, the most common answer here was “short” reviews: half of respondents cited reviews that are “less than 5 lines” or that “span a single paragraph and don’t give me anything to learn from,” with “no justification and little feedback.” But long reviews can also offend: “very long reviews that criticise work severely from a very particular viewpoint.”

Several said they were bothered most by rude reviews, such as one that “is dismissive or sounds angry” or that gives the “insinuation that we had no clue.” Another pointed to “reviews that assume a certain gender or country of origin for authors.”

A few cited a lack of care: “Sometimes reviewers clearly just don’t read their assigned papers carefully.” The outcome may be a short, cursory review, as above; or, it could lead “the reviewers [to] ask a question that has already been answered in the paper”; or, it could lead to “a very bad review based on a strong misunderstanding of the paper.”

Most respondents mentioned one of the above points. However, not everyone had a grievance to share: one wrote that “I generally receive excellent reviews at ISMIR”; another that “I do not have any complaints on the reviews I receive, which are almost always excellent when viewed as a whole for a given paper.”

Question 20. What do you appreciate about the reviews you receive?

As with the previous question, respondents were remarkably consistent when answering this free-response question: 60% of respondents said that they most appreciate “constructive feedback”: “suggestions to improve my research” and “make the paper better” — especially “in a way that is doable.”

What kinds of suggestions are appreciated? Reviewers may “point to missed references” or “describe links that I missed”; they may “have suggestions for how to make methods or results more accessible to a broader ISMIR (and ISMIR-interested) audience.”

Hearing from readers with “another perspective” is of great value, especially “those with specialities a little different from my own.” For example, “the first paragraph [summarizing the paper] written by a reviewer makes me understand whether my presentation is clear and convincing.”

Another common refrain: authors simply appreciate that “people took the time to read my paper”; that “they care.” One way reviewers show care to a paper is “show[ing] that they understand it.”

Several praised the high quality of their ISMIR reviews, with one writing: “I’ve received many very thoughtful reviews with lots of carefully thought-out detail that helped me make my papers better!”

Parting words

Our survey respondents wrote that they appreciate the time and feedback of other reviewers. Similarly, we are hugely thankful for the time that our respondents spent filling out this survey!

If this blog post is too long, it is still much shorter than all the responses we received. We hope it transmits much of the wisdom we collected, but we know it does not, and so we look forward to continuing this conversation about reviewing at the 2021 edition of ISMIR and in future years.